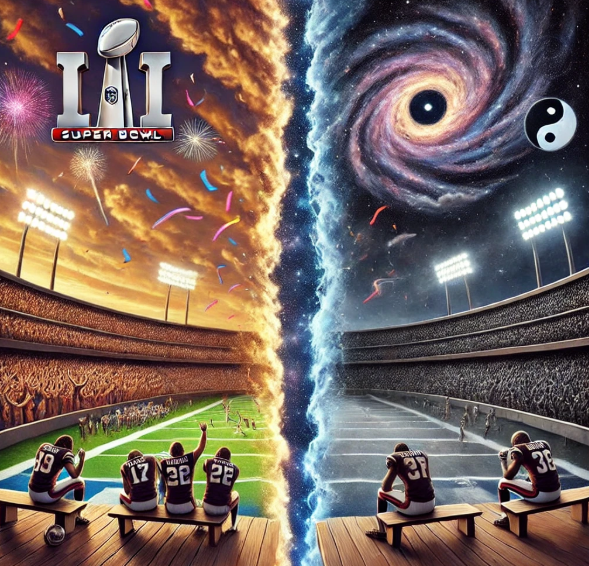

The Super Bowl is a grand spectacle, a ritual that captivates millions with its clear-cut narrative of heroes and villains, winners and losers. It offers something deeply satisfying to the human mind—resolution. A game ends with a champion and a defeated opponent. The finality is intoxicating. The binary nature of competition feels true, as if it reflects something fundamental about reality itself. But does it?

Beneath the roar of the stadium, the triumphs and the heartbreaks, lies a far more complex truth—one that is not easily captured by two opposing forces. Our attraction to binary thinking, to seeing the world in terms of black and white, good and evil, success and failure, is less about reality and more about how our minds make sense of it.

The Paradox of Opposites: Can One Exist Without the Other?

Language itself relies on opposition. We define things not only by what they are, but by what they are not. There is no black without white, no up without down, no foreground without a background. Try to imagine a single color with no contrast, or a shape that exists without space around it. Even selfhood—our internal sense of identity—is shaped in contrast to the external world. But are these distinctions real, or are they just the brain’s way of carving the world into manageable chunks?

In physics, we see that what appears separate is often inseparable. A wave cannot exist without the ocean. A flame needs oxygen. The observer and the observed influence each other at a quantum level. The idea of absolute separation begins to dissolve the closer we examine it.

This is not just true in the physical world, but in human experience. Take recovery and addiction. Many people I meet in recovery describe the moment their addiction ended as the day they stopped using. A clear boundary. Abstinence begins, and addiction is over. But was that the true beginning of recovery? Or did the unraveling start much earlier—perhaps long before the first drink, when trauma, disconnection, or survival mechanisms were taking root? And what about the behaviors that persist long after abstinence—compulsions, deception, selfishness? If addiction is only about substance use, then what do we call these patterns when the substances are gone?

The more closely we look, the more the boundary between addiction and recovery dissolves from abstinence to lasting transformation.

The Comfort of Two Choices vs. The Discomfort of Complexity

Binary thinking is powerful because it simplifies decision-making. It gives us a side to pick. It creates moral clarity. But this clarity is often an illusion—one that leaves us polarized and trapped in rigid frameworks.

Even in personal growth, we see this struggle. Is selflessness a real thing? Or is the process of becoming selfless actually a deep recognition that the self was never truly separate to begin with? That what we think of as “our mind” is not an isolated entity but something shaped by culture, language, and shared experience?

We don’t invent the language we think in. We download it. Our thoughts, beliefs, and even our sense of identity are borrowed from the world around us. In this sense, the boundaries we place between self and other, internal and external, are not as fixed as they seem.

Conclusion: A New Way to See the Game

So perhaps the Super Bowl—the grandest stage of binary competition—is not just about victory and defeat. Perhaps it mirrors something deeper about our desire for clarity, for a world that can be neatly divided into opposites. But the truth of life, like the truth of addiction and recovery, is rarely so simple.

Winning and losing are not endpoints. They are moments in a much larger, interconnected story. The game may end, but the players wake up the next morning, changed, but not defined, by the outcome.

And so do we.

Sources:

- Watts, Alan. The Wisdom of Insecurity: A Message for an Age of Anxiety.

- NFL Super Bowl History Archives.

- Harari, Yuval Noah. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind.

- Klein, Naomi. The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism.