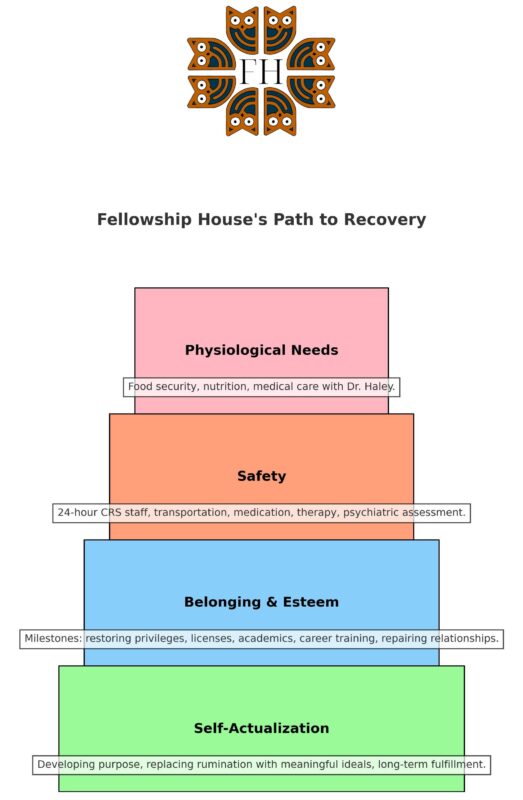

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs provides a useful framework for understanding the progression of healing in Substance Use Disorder (SUD) recovery. The foundational levels—physiological needs, safety, and social belonging—align closely with the early stages of recovery and the principles found in the 12-step model. At Fellowship House, we see these needs play out daily as individuals transition from survival-based thinking to higher cognitive and emotional processing.

The Base of the Pyramid: Physiological and Safety Needs

At the bottom of Maslow’s pyramid are physiological needs: food, water, and shelter. Traditional recovery models often emphasize a strong desire for change before addressing these material needs, but history tells a different story. In the early years of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), members ensured newcomers had food, a safe place to live, and a sense of stability. This practical support laid the foundation for lasting recovery. Without these basic needs met, expecting someone to engage in deep therapeutic work is unrealistic.

Once an individual secures their basic needs, the next level—safety—becomes essential. Safety in recovery means more than physical security; it includes emotional stability, structured routines, and reliable relationships. At Fellowship House, the first two weeks often bring a kind of “limping ego”—individuals navigating new social dynamics, assessing trust, and determining where they fit. When safety is established through routine, dignity, and respect, the nervous system begins to settle, allowing for deeper work to begin.

Orders of Consciousness and the Evolution of Survival Priorities

The first order of consciousness revolves around agency—our ability to act within our environment. Consider a squirrel storing nuts: this behavior appears deliberate but is largely an instinctual response rather than conscious planning. Humans, too, operate on a similar level when faced with extreme fatigue, trauma, or dissociation. When the brain is overwhelmed, it defaults to survival autopilot, a mode deeply rooted in our evolutionary past, dating back well before the Bronze Age.

Around 12,000 years ago, major transformations in human survival priorities emerged, driven by the division of labor, identity formation, economic structures, and social norms. These abstract systems, while essential to modern civilization, can overburden a nervous system originally designed to measure mortal threats in a much simpler world. Today, many of the stressors that trigger survival responses—financial instability, social rejection, or existential uncertainty—may not be life-threatening, yet the brain reacts as though they are.

Our individual experience of these stressors is shaped by variables beyond our control in early life: socioeconomic conditions, education, and social environments. These factors mold our cognitive framework, influencing how we process discomfort, abstraction, and social cues. Once we surpass the hurdle of recognizing that we are truly safe—and, in fact, have been for most of our lives—the path to self-actualization can accelerate.

The Inverted Pyramid: Addiction’s Reverse Path

While Maslow’s pyramid represents growth, addiction often follows an inverted trajectory. Self-actualization, in its illusionary form, is first achieved artificially through substances—offering a fleeting sense of relief and relaxation. This momentary state mimics the peace and confidence that real self-actualization provides but is unsustainable and fragile.

As addiction progresses, individuals move backward down the pyramid. Social connections deteriorate, safety is compromised, and physiological needs become unstable. The insidious nature of addiction is its reverse workflow—it hijacks the hardwired structures of the brain, convincing it that survival depends on substances. Over time, the brain’s patterns, shaped by trauma and reinforcement, cement these behaviors as the default response to discomfort.

The Mid-Level: Social Connection and Psychological Safety

The third level of Maslow’s pyramid—social belonging—mirrors the third step in AA’s 12-step process. Connection with others in recovery is crucial for long-term success. Humans, like all mammals, are wired for social survival. In SUD recovery, this manifests in forming friendships, identifying safe mentors, and engaging in group therapy.

Research into fight, flight, and freeze responses shows how individuals under chronic stress operate primarily from their midbrain, driven by instinct rather than higher reasoning. Navy SEALs, for example, are trained not to fight but to freeze—allowing their cognitive brain to take control, assess the situation, and strategize within seven to thirty seconds. In recovery, something similar happens: once a person feels physically safe and socially supported, they can move beyond impulsive, survival-driven reactions. They begin operating from the prefrontal cortex—the center of reason, logic, and long-term planning.

Beyond Survival: The Spirituality of the Frontal Lobe

When the lower levels of Maslow’s pyramid are secured, a shift occurs. Individuals in recovery begin to engage in meaningful actions not for external validation but from an intrinsic sense of purpose. Esteem grows not through artificial reinforcement but through real accomplishments—working towards goals, repairing relationships, and embracing curiosity about life beyond addiction. Self-actualization is not a distant, 20-year goal; it can emerge in months when a person realizes they are safe, accepted, and capable of growth.

This phase of recovery can still be described as spiritual. The spirituality of the frontal lobe emerges when individuals gain the ability to see life with deeper meaning, guided by ideas, virtues, and authentic connections. Once the primal survival instincts—the “werewolf” of the midbrain—are turned off, navigating recovery becomes like riding a bike. At Fellowship House, we believe that once a person learns how to engage with their higher faculties, they can always return to this mindset to prevent relapse or crisis. When the foundation of the pyramid is firm, the individual can build a life of stability, fulfillment, and meaning.

Building a New Pattern: Recovery as a Cognitive Software Shift

The key to reversing the downward trajectory of addiction is not merely in changing the brain but in changing its patterns. The mind can be reprogrammed like software through behavioral shifts, new cognitive approaches, and structured routines. Daily practices like proper diet, consistent routines, and stress resilience training help override the old scripts that addiction has embedded in the nervous system.

At Fellowship House, we encourage a framework that prioritizes meaning and purpose over fear responses. By practicing new ways of engaging with discomfort—rather than running from it—individuals strengthen the neural pathways that support long-term recovery. This resilience-building allows individuals to reclaim their sense of self and autonomy, ultimately making relapse prevention a natural byproduct of a well-structured, meaningful life.

Investing in Material and Psychological Growth

At Fellowship House, we do more than provide therapy. We invest in the material lives of our clients—helping them clear licenses, resolve fines, obtain work permits, and develop plans for their future. We meet them halfway, proving that they are worth the effort. When you change the material conditions of someone who now feels safe and supported, you give them a tangible leg up in the world.

Conclusion

Maslow’s framework reminds us that sustainable recovery requires more than abstinence or therapy alone. It demands a holistic approach that stabilizes material conditions, fosters emotional safety, and builds genuine connections. Only when these foundational needs are met can individuals truly move toward self-actualization, achieving lasting recovery and a life of meaning beyond addiction.